Last week, Islamist sect Boko Haram bombed a bus station just outside the Nigerian capital of Abuja. That same day, as authorities were tabulating a body count from the explosions that would eventually reach 71, Boko Haram militants disguised as Nigerian soldiers kidnapped over 200 girls from a school in the country’s northeast.

Several of the girls have since escaped, but the majority are still missing and there is a growing fear that most of these girls — aged 15 to 18 — are likely to be used as cooks, servants and sex slaves by Boko Haram.

Though the dual attacks were particularly pernicious, Boko Haram and its offshoots have been launching deadly attacks throughout northern Nigeria for the better part of five years. 2014 is proving to be a particularly lethal year, with at least 1,500 dead since January.

With some notable exceptions, most of the violence surrounding Boko Haram has been limited to Nigeria’s northeast. Concrete details of the horrific, day-to-day violence rarely register in the south of the country. In Nigeria’s largest urban center, the megacity of Lagos, news of the bloody insurgency is often reported with the indifference of a weather update.

But incidents like the bombing in Abuja, which spark nationwide outrage and garner international attention, are almost always accompanied by a proliferation of articles that aim to explain the structure, ideology and goals of Boko Haram.

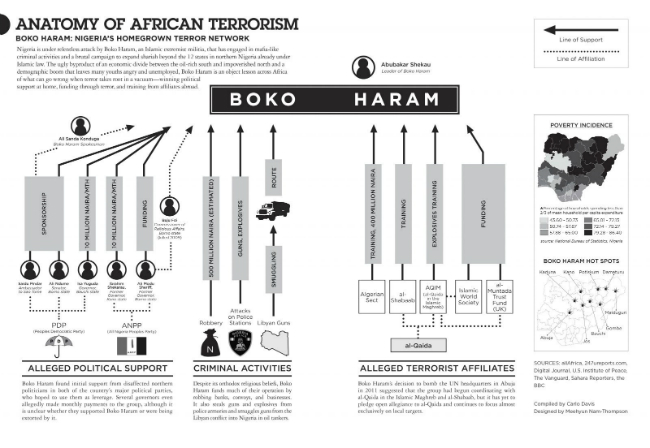

This chart, via the World Policy Journal, is among the better efforts to be widely circulated in the past week:

Yet the fact remains relatively little is known about Boko Haram considering the destruction the group has wrought. Grappling with the nihilism associated with Boko Haram is a difficult and thoroughly unsettling undertaking, in part because the more we learn about the group and its war against the Nigerian state, the more intractable the conflict seems.

To the extent that the group can even be considered a cogent organization or a singular movement, Boko Haram is at once an Islamic extremist militia and a mafia-like crime syndicate. It offers northern Nigerians a radical alternative to the status quo and wins over young recruits by tapping into deep dissatisfaction with the current political system. It sustains itself through ideological appeal and local support, but also through collusion with corrupt or sympathetic state and military officials. In addition to local patronage, Boko Haram earns cash through criminal activity and from benefactors abroad.

The goal of this article is to contextualize Boko Haram. It is an attempt to fill in the gap between journalistic accounts and existing academic literature in a way that is accessible to readers who wish to better understand Boko Haram, its historical basis, and the current socio-political environment in which it operates. A list of non-journalistic works, to which this article is heavily indebted, is included at the bottom of the page.

Nigeria in Context

Nigeria represents the best and worst of how African states are perceived by the broader international community, and the paradox of Nigeria rests in its ability to be an economic giant and a regional leader all while being best known — much to the chagrin of Nigerians — for its chronic dysfunction.

With a population close to 175 million and rapidly growing, Nigeria is by far the most populous country in Africa. It is a country of immense natural wealth, boasting large swaths of productive agricultural land and enormous deposits of oil, natural gas, and minerals. Add in an urbanization rate of close to 50% and a population with a median age of less than 18, and it is easy to see why many analysts see Nigeria as a country poised for economic prosperity.

Already the largest oil producer in Africa, Nigeria’s economy has been growing at a rate of 6 to 7 percent per year and earlier this month, after a re-assessment of GDP, it came out ahead of South Africa as Africa’s largest economy.

Nigeria possesses one of Africa’s strongest and most capable militaries, which has played an active – though not always well received – role in peace operations abroad. At the international level, Nigeria takes on leadership roles within major international organizations such as the Organization of the Islamic Conference, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, the African Union and the Economic Community for West African States.

But Nigeria’s economic growth comes in spite of endemic corruption, grinding poverty (70 percent of Nigerians live below the poverty line), and decades of sectarian violence. Furthermore, the country suffers from what can only be called a terrible reputation abroad.

“They just tend not to be honest,” said Colin Powell in 1995. “Nigerians as a group, frankly, are marvelous scammers. I mean it is in their national culture,” Powell continued, wondering what Nigeria could have done with all its wealth had it not “just pissed it away.”

In film, literature, and even US politics, Nigeria is the go-to shorthand for corruption and graft. When the likes of Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe express concern that his citizens are so corrupt that they are “acting like Nigerians,” it is safe to say that Nigeria has an image problem.

Unsurprisingly, Nigerians resent these caricatures. Nigeria perceives itself as the natural leader of the African continent. Nigerian commentators are often quick to accuse African critics of jealousy and Western critics of racism (and there are plenty of actual cases of both).

Yet the way in which Nigerians perceive themselves and their place in the world is not simply a matter of the demographic and economic realities mentioned above. As I wrote from Nigeria for Beacon earlier this year, a current of “Nigerian exceptionalism” runs through much of the domestic discourse:

Nigerian exceptionalism, like its American counterpart, is a double-edged sword. It is the source of an admirable arrogance that fuels innovation and at the same time, it is the root of a crippling tendency to dismiss unflattering critiques that come from outside its borders. Here, the claim that Nigeria is the future of the African continent is treated as self-evident and a belief that this future is a bright one is taken as gospel – sometimes literally.

Merely labeling Nigeria as a country that has squandered its potential, however, is a lazy intellectual gambit. The roots of Nigeria’s dysfunction, and the fault lines along which Nigeria may be torn apart, can be traced to the very process of its formation, a process for which Nigerians themselves can hardly be blamed.

As McLoughlin and Bouchat explain:

Like most post-colonial African states, Nigeria is both a mosaic of tribes, related or allied ethnic or ideological groups, and nations now linked economically and politically under a common government in a colonially imposed territorial unit. The British colonial government created a unified Nigeria in 1914 to demarcate its area of control from those of its European competitors and because its northern protectorate was too poorly resourced to stand on its own. It was therefore created as a state by externally imposed fiat, not for any internal, organic reason. Before the British arrived, there was no shared national consciousness, culture, or language in Nigeria, nor was there any sentiment to coalesce its peoples into a coherent nation under colonial rule.

Dysfunction by Design

In the early 1900s, the British Empire extended its colonial reach northward from the Nigerian coast, eventually gaining control of what was then the Sokoto Caliphate. The British initially decided to maintain northern and southern Nigeria as two separate protectorates due to their cultural differences, but economic considerations led the British to merge the two in 1914.

Even after unifying northern and southern Nigeria, Britain pursued a colonial system of indirect rule in the north, choosing to govern the area through preferred indigenous rulers. The effects of this policy, which institutionalized existing north-south divisions, as well as divisions within northern Nigeria, are prevalent to this day.

Though outsiders tend to dwell on Nigeria’s general dysfunction, it might be more appropriate to marvel at fact that 53 years into independence, Nigeria has managed to remain a single state. While the Biafran war of the late 1960s is the most internationally well-known manifestation of regionalist and sectarian impulses in post-colonial Nigeria, it is by no means the only one. The Federal Government continues to face challenges to its authority from a number of armed groups operating on regional, ethnic, ideological and religious motivations to this day.

The Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra operates in the southeast, while the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People and the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta in the south. Like Boko Haram in the north, all of these movements are fighting in different ways to wrest control of territory (and resources) from the central government.

Contemporary Politics

Governing such a divided state was never going to be an easy undertaking, but many of the compounding difficulties Nigeria faces today are of its own making. The string of military juntas that ran Nigeria into the ground for much of its existence only gave way to democracy in 1999, and Nigeria’s current government has done little to inspire confidence.

The democratic transition in 1999 saw the election of Olusegun Obasanjo, making him the first Christian and southerner to lead the federal government since his own tenure as a military ruler from 1976 to 1979. This shift in political power from northern political elites to southern political elites, combined with widening economic disparities between north and south, fueled a sense of political marginalization throughout much of northern Nigeria.

Nigeria’s economic decline since independence also hit the north particularly hard. Development indicators remain lower than in the south, where there is far more public and private investment, and infrastructure and health services are more developed. Per capita public expenditure on health in the north was less than half that in the country’s south as recently as 2003. In some parts of northeastern Nigeria, the heart of the Boko Haram, youth unemployment is estimated at 80 percent.

Decades of corruption, abuse, and inept government have left a chasm between the government and the governed. Lacking faith in their government and politicians, millions of Nigerians have turned to individuals and groups that advocate a radical alternative to the status quo, which is often expressed in religious or moral terms.

Within Christian communities, based predominantly but not exclusively in southern Nigeria and constituting roughly 40% of the population, disillusionment with government correlates with a rise of evangelical Christian movements advocating faith as an alternative means to health and economic prosperity. Among Nigerian Muslims, who are based predominantly in the north and comprise approximately 50% of the population, there has been a surge in support for sharia law as an alternative to a corrupt and ineffectual secular judiciary.

(Political) Islam in northern Nigeria

Islam was first introduced to northern Nigeria in the 11th century. The religion took root in the major urban centers across the north and gradually spread south into what today is referred to as the “middle belt” of Nigeria by the 16th century.

Since 2000, 12 states in northern Nigeria have codified sharia law within their legal codes. Though the vast majority of Nigeria’s Muslims are Sunni, there is a significant Shia minority. A wide array of brotherhoods and sects advocate various forms of violent and non-violent fundamentalist, conservative, and moderate Islam.

Northern Nigeria has a rich tradition as a center of Islamist thought, including fundamentalist strands of Islam, which dates back centuries. One of the first and most famous instances of armed Islamist uprisings against the state came in the early 19th century when religious scholar Usman Dan Fodio led ethnic Fulani Muslims in a rebellion against the dominant, ethnic Hausa sultanates as well as the powerful sultanate of Borno.

Dan Fodio’s political and social revolution was guided by the belief that the rulers of northern Nigeria were corrupt and were not true religious adherents because they allowed the practice of Islam to be mixed with traditional beliefs. After initially leading his followers into exile, Dan Fodio called for jihad and returned to successfully topple the existing political order. He would go on to establish the Sokoto Caliphate, which stretched across northern Nigeria and its environs.

To this day, the Sultan of Sokoto remains one of the most important and influential religious leaders in northern Nigeria, and the halcyon days of Dan Fodio’s caliphate are referenced widely as an example of Islamic resistance to corrupt, secular government.

Islamic resistance movements have subsequently adapted to Nigeria’s modern context. Peter Chalk identifies three main streams of Islamic thought in contemporary Nigeria: conservatism, modernism and fundamentalism. According to Chalk, fundamentalism in the Nigerian context focuses on “anti-system movements that articulate vehement opposition to the existing political (secular) status quo, the federal government, established (and perceived ineffectual) religious elites, modern-oriented Muslim identity, and foreign – mainly Western – influences.”

Over the last ten years, Boko Haram has emerged as the most salient and destructive manifestation of this philosophy.

Boko Haram in Context

Initially established as a religious movement in the late 1990s/early 2000s, Boko Haram seeks to purify northern Nigeria from the corrupting influences of Western culture. The group has since transformed into an armed insurgency determined to transform Nigeria into an Islamic state.

Though Boko Haram has been active for the better part of a decade, the movement burst onto the international scene in 2010 and 2011 after a string of deadly attacks against the Nigerian government. The highest-profile incident among these was an attack on the United Nations building in Abuja, in which Boko Haram killed 23 people with a car bomb.

In the last year alone, Boko Haram has deployed suicide bombs and coordinated assaults on an array of targets, including markets, schools, bus stations, hospitals, clinics, banks, churches, mosques, police stations, government buildings, and military installations.

Amid an upsurge in violence, Nigerian citizens are openly wondering if their country is on the brink of a civil war. On a recent overland trip from Kaduna to Abuja, I counted no less than 20 checkpoints on a 220 kilometer stretch of road in an area not really considered a hotbed of Boko Haram activity. An air of apprehension pervades daily life throughout much of northern Nigeria, with social and economic activities in various communities grinding to a halt. Previously peaceful communities are becoming fractured.

While Boko Haram appears to be growing more lethal – the group is thought to have killed thousands since 2009 and carried out several audacious large scale attacks on heavily fortified military targets in the last few months – precious little is known about its leadership, organizational structure, funding streams, and membership. At any given time, a patchwork of armed groups or individuals in northern Nigeria may be carrying out attacks under the banner of Boko Haram.

Even its name, “Boko Haram” – a phrase borrowed from northern Nigeria’s Hausa language – is an unofficial moniker ascribed from the outside that the group’s core members do not use, preferring its official Arabic name of “Jamā’a Ahl al-sunnah li-da’wa wa al-jihād” instead.

Despite its Hausa moniker, the majority of its initial membership is believed to be ethnic Kanuri, from northeastern Nigeria. Over the course of the last decade, however, the group has metastasized, spreading throughout northern Nigeriaand inserting itself into longstanding conflicts in Nigeria’s “middle-belt.”

Boko Haram has also extended its reach into southern Niger and northern Cameroon, where it can take advantage of long, porous borders to regroup and recruit within Kanuri communities outside of Nigeria. Last month, a local official in southern Niger told me that he knows Boko Haram “weekends” in Niger, but he does not have the means or mandate to do anything about it.

And while the scope and intensity of Boko Haram’s terror campaign is breathtaking, the movement is not without local precedent.

As previously discussed, Dan Fodio’s legacy of a purifying withdrawal from society in order to wage a righteous jihad against corrupting influences is seen by many northern Nigerian Muslims, including Boko Haram, as a template for a more just and equitable society.

More recently, the Maitatsine movement has assumed the mantle. The group’s leader, a Cameroonian preacher named Mohammed Marwa, took up the teachings of Dan Fodio after arriving in the northern Nigerian city of Kano in 1945.

Marwa’s preaching, predicated on the belief that he himself was a prophet, earned him the name Maitatsine, which translates from Hausa to mean “he who curses” or “the one who damns.” Much like Dan Fodio, Marwa’s movement stood against Nigeria’s corrupt secular government and its allies within the “moderate” religious establishment. Seeing the danger in his message, the British colonial government forced Marwa into exile. He would return to Kano shortly after independence in the 1960s.

The Maitatsine message resonated with the young, poor and unemployed in the slums of Kano, northern Nigeria’s largest city, and during the 1970s, the movement gradually turned violent, clashing with police and state authorities.

Marwa was killed in 1980 during a confrontation with police, but even after his death, riots spread throughout northern Nigeria, claiming the lives of between 4,000 and 5,000 people. The movement never quite recovered, but isolated pockets of extremism remained, and Maitatsine teachings are thought to be a source of ideological inspiration for Boko Haram.

The Maitatsine movement introduced many of the tactics that would become common in northern Nigeria’s current wave of Islamic radicalization. Several violent and non-violent radical movements in northern Nigerian, for example, have sought to mobilize poor communities against established, urban Muslim elites perceived to be colluding with a corrupt, secular government.

The success of the heavy-handed tactics used by the Nigerian government to crush the Maitatsine movement may have given a false sense that Boko Haram was merely the latest manifestation of a violent Islamist undercurrent that could be stemmed through similar means.

To the contrary, by all accounts, attempts to crush Boko Haram through military might have proved unsuccessful, and have likely exacerbated the problem.

In 2003 and 2004, for example, Nigerian security forces cracked down on Boko Haram during mass uprisings and thought the problem had been dealt with, only to see Boko Haram re-emerge.

A 2009 attempt to deliver a decisive blow to Boko Haram in their stronghold of Maiduguri led to the death of at least 700 people. Boko Haram’s leader at the time, Mohammed Yusuf, was captured by police and summarily executed. After that episode, Boko Haram temporarily faded from public view, but came back a year later more determined and lethal than before.

Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan – a Christian from the south – has sought to crush Boko Haram through the enlistment of civilian vigilante groups and the deployment of some 8,000 soldiers to northern Nigeria, supported by fighter jets and helicopter gunships. Due to a virtual media blackout in northeast Nigeria, where a state of emergency has been in place since May 2013, very little information can be independently verified. In official reports, the Nigerian government often downplays its own casualties while inflating the number of Boko Haram militants killed in a given battle. Consequently, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of the Nigerian government’s heavy-handed tactics, and the impact fighting between the government and Boko Haram has had on the civilian population.

During its operations against Boko Haram, the Nigerian government has allegedly killed hundreds of suspected militants and sympathizers since 2009. The military has burned homes and executed suspected Boko Haram members in front of their families. In addition to extrajudicial killings, military officials and politicians stand accused of using Boko Haram as a cover for attacks on political rivals or as pretext for score-settling.

Nigerian authorities have also arrested thousands of people across northern Nigeria, holding many of these prisoners incommunicado without charge or trial for months or even years. In some cases, prisoners have been detained in inhuman conditions, tortured or even killed. Amnesty International reportedreceiving credible evidence that over 950 people died in military custody in the first six months of 2013 alone.

The ongoing violence and abuse by government forces may even be driving new recruits to join Boko Haram, reaffirming Boko Haram’s message that the government is an enemy of the people. Boko Haram and its followers appear all the more driven by a desire for vengeance against politicians, police, and Islamic authorities aligned with the state.

Part of what makes understanding and defining Boko Haram so difficult is the fact that it may very well be several different things at once. Boko Haram has proven itself very adaptable, evolving its tactics swiftly and changing its targets at the behest of a charismatic, if opaque leadership.

As former US ambassador to Nigeria John Campbell told reporter Andrew Walker, Boko Haram is certainly a grassroots movement that taps into anger over poor governance and a lack of development in northern Nigeria. Yet it is also a core of Mohammed Yusuf’s followers who have reorganized around the group’s new leader Abubakar Shekau to exact revenge on the Nigerian state. At the same time, Boko Haram can be viewed as a kind of personality cult, an “Islamic millenarianist sect” inspired by a charismatic preacher.

The increased sophistication and lethality of Boko Haram’s attacks are often cited as evidence that they are collaborating with foreign groups, and its membership is believed to have diversified. Though experts and analysts are not in total agreement, there is some anecdotal evidence that may suggest foreign fighters from Chad, Mauritania, Niger, Somalia and Sudan have joined Boko Haram.

Splinter groups emerging from Boko Haram have also emerged, the most prominent being the group commonly referred to as Ansaru, which formed in 2012 (its full Arabic name, Juma’atu Ansarul Muslimina Fi Biladis Sudan, translates to “Vanguards for the Protection of Muslims in Black Africa”).

Ansaru explicitly targets Westerners in Nigeria and neighboring countries, and some analysts cite this goal as possible evidence that the once parochial ambitions of Boko Haram, or factions within Boko Haram, may now be international. Since 2011, there have been increasing signs of international collaboration between Boko Haram and militants from Niger, Mali, the broader Sahel, Somalia and other countries throughout the Muslim world, but the extent to which Boko Haram and its variants have gone international is still widely debated among those who follow the group.

For its part, the US government has placed a $7 million bounty on the head of Boko Haram’s leader, Abubakar Shekau. Shekau heads a list — released in June as part of the US State Department’s “Rewards for Justice” program — offering $23 million worth of rewards for information on key leaders of terrorist organizations responsible for a string of deadly attacks and kidnappings throughout North and West Africa.

In November of 2013, the US State Department took the additional step ofofficially designated Boko Haram and Ansaru as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations and as Specially Designated Global Terrorists.”

No End In Sight

Nigerian government attempts to negotiate with Boko Haram have proved as unsuccessful as efforts to crush the group militarily.

In 2011, for example, democracy activist Shehu Sani tried to arrange exploratory talks between the former president Olusegun Obasanjo and Babakura Fugu, the brother-in-law of Boko Haram’s then leader, Mohammed Yusuf. Soon after the meeting, gunmen stormed into Fugu’s house and shot him dead. Boko Haram denied the killing and the assassins have not been identified (note: some have argued that Fugu was actually killed in police custody).

In January 2012, a group claiming to be a moderate breakaway faction of Boko Haram sent a tape to the National Television Authority stating readiness to negotiate. Four days later, a dozen people were publicly beheaded in Maiduguri by militants claiming to be Boko Haram.

Even in the face of these setbacks, the administration of President Goodluck Jonathan has demonstrated intermittent interest in the idea of dialogue with Boko Haram. The formation of the Committee on Dialogue and Peaceful Resolution of Security Challenges in the North of Nigeria, formed on April 24, 2013 is probably the most ambitious overture to date, but there are several practical and political barriers to productive negotiations taking place.

Some of Boko Haram’s stated demands are impossible to realize, and often contradictory. The demand that Nigeria implement Islamic law nationwide, for example, is a non-starter.

Thanks to Boko Haram’s diffuse, cell-like organizational structure, finding credible representatives of the group who are serious about negotiations may not be possible. Even if it were possible, it is unclear that these representatives or interlocutors would be able to control other factions within Boko Haram.

It is also unclear what exactly Boko Haram has to offer the government short of dropping its core demands in the first place.

Nigeria’s 2015 Presidential elections, which will be hotly contested and likely lead to violence, represent another barrier to a negotiated solution. Offers of amnesty and calls for negotiations are sure to be politically unpopular with Christians and the vast majority of Muslims in Nigeria who oppose the group. The collapse of previous ceasefires and attempts at negotiations, combined with the growing impatience of communities affected by the crisis, is likely to strengthen the hand of those who prefer a military solution.

Political imperatives suggest that the Nigerian government is likely to continue a military approach to defeating Boko Haram in the near term, but as researcher Alex Thurston writes, “the limitations of military approaches may soon lead Nigeria back to the hope of dialogue, and the difficult question of how to break the cycle of ineffective crackdowns and inconclusive negotiations.”

Perhaps the most disquieting truth about the crisis in northern Nigeria, however, is that so many individuals on both sides of the conflict have vested political and economic interests in its continuation. So long as Boko Haram is a convenient enemy and useful pretext for powerful individuals, whether they be politicians, military officials or even local elites in northern Nigeria, the conflict is likely to continue for the foreseeable future.

Works Referenced:

- Clarence J Bouchat, “The Causes of Instability in Nigeria and Implications for the United States,” Strategic Studies Institute, 19 August 2013.

- Gerald McLoughlin and Clarence J. Bouchat, “Nigerian Unity In The Balance,”Strategic Studies Institute, June 2013.

- Jonathan N.C. Hill, “Sufism In Northern Nigeria: Force For Counter-Radicalization?” Strategic Studies Institute, May 2010.

- Carlo Davis, “Boko Haram: Africa’s homegrown Terror Network,” World Policy Journal, 12 June 2012.

- Emilie Oftedal, “Boko Haram: An Overview,” Norwegian Defense Research Establishment (FFI) 31 May 2013.

- Abimbola Adesoji, “The Boko Haram Uprising and Islamic Revivalism in Nigeria,” Africa Spectrum 45, no. 2 (2010)

- Peter Chalk, “Islam in West Africa: The Case of Nigeria,” in The Muslim World after 9/11, ed. Angel M. Rabasa et al. (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2004).

- Hakeem O. Yusuf, “Harvest of Violence: the Neglect of Basic Rights and the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria,” Critical Studies on Terrorism, Volume 6, Issue 3, 2013.

- N. D. Danjibo, “Islamic Fundamentalism and Sectarian Violence: The ‘Maitatsine’ and ‘Boko Haram’ Crises in Northern Nigeria,” Peace and Conflict Studies Programme, Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan.

- Michael Olufemi Sodipo, “Mitigating Radicalism in Northern Nigeria, African Center for Strategic Studies, No. 26, August 2013.

- David Cook, “The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria”, CTC Sentinel 4, no. 9 (2011).

- Andrew Walker, “Special Report: What is Boko Haram?” United States Institute of Peace, June 2012.

- Rom Bhandari, “Boko Haram Infiltrates Government,” Think Africa Press, 10 January 2012.

- Alex Thurston, “Nigeria: An Ephemeral Peace,” The Revealer, 22 June 2013.

- Human Rights Watch, “Nigeria: Massive Destruction, Deaths From Military Raid,” 1 May 2013.

- Amnesty International, “Nigeria: Deaths of hundreds of Boko Haram suspects in custody requires investigation,” 15 October 2013.

- Peter Dörrie, “Nigeria is at War with Islamist Ghosts,” War is Boring, 10 September 2013.

- Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram’s Dangerous Expansion into Northwest Nigeria,” CTC Sentinel, 29 October 2012.

- Jacob Zenn, “Boko Haram’s International Connections,” CTC Sentinel, 14 January 2013.

- Jacob Zenn, “Nigerians in Gao: was Boko Haram really active in Northern Mali?”African Arguments, 20 Janaury 2014.

- Jacob Zenn, “Cooperation or Competition: Boko Haram and Ansaru After the Mali Intervention,” CTC Sentinel, 27 March 2013.

Peter Tinti is an independent journalist covering politics, culture and security in West Africa. Formerly based in Bamako, Mali, he is currently traveling between several countries throughout the Sahel/Sahara. Visit his website here

Among other outlets, Tinti’s writing and photography has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Foreign Policy, World Politics Review, Christian Science Monitor, Al Jazeera, The Independent, The Telegraph, and Think Africa Press. He also publishes on Beacon.

In 2013, Action On Armed Violence included Tinti in its list “Top 100: The most influential journalists covering armed violence.”

This article first appeared in Beacon Reader